Every year, Ada Lovelace Day rolls around, reminding the world that yes, we do need to reach out in support of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics). To defend this assertion, this year I’m only putting forward two pieces of evidence: #timhunt and #shirtgate, both of which happened in the year since the last Ada Lovelace Day.

And with that justification, here’s my contribution, countering the seemingly ingrained misogyny within the world of STEM with my celebration of female contributions to science.

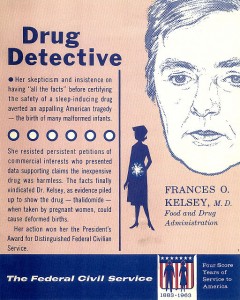

In 1960, Canadian pharmacist and physician Frances Oldham Kelsey was hired by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Washington, D.C., to review drug applications for licensing in the United States. Since Kelsey had experience in placental drug transfer, teratogens and pharmaceutical safety, it is perhaps fitting that one of the first drug approvals to land on her desk was Richardson-Merrell’s application for thalidomide.

Thalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug with effective sedative properties in humans, had been available since 1957 (in Germany) and was a drug of choice for treating morning sickness during pregnancy. Since it had widespread acceptance in Europe and Australia, the drug’s distributors expected early acceptance in the United States, and indeed sent out advance clinical trial dosages to interested GPs.

However, Kelsey and her co-workers, troubled by gaps and inconsistencies in the research data supplied along with the application, requested further information on safety trial findings. In the end, Kelsey refused to accept the application not once—but a whopping six times. In the face of continual pressure from the applicants, she held out long enough for the news of the appalling adverse effects of taking the drug during pregnancy to reach the medical press; in November 1961, thalidomide was taken off the market. Only 17 children were born in the United States with thalidomide-induced damage, compared to 5,000–7,000 in Germany, where the drug was freely available over the counter, and around 1,000 in the United Kingdom. In Canada, where the drug remained available until March 1962, the number of thalidomide victims remains unknown, with the 92 surviving victims just recently receiving compensation.

What impresses me most about Kelsey’s story is her tenacity, especially during the era in which she held strong to her convictions. I’m completely blown away that one woman, a young physician in her mid-twenties working in the pre-feminist era of Mad Men with all its attendant misogynistic, gender-debasing, anti-women rhetoric, would stand up to a pharmaceutical giant and say no!

She may not have had to face That Shirt in her workplace, but I wonder how many offices she walked into in her daily life with pin-up calendars nonchalantly adorning the walls. Heck, they were still there on the walls in the 1970s, when I started to take notice. And even if “the trouble with girls …” was not muttered behind this brave woman scientist’s back, I wonder how often she was demoted to the juvenile descriptor “girl” or referred to by her first name to keep her in her “proper” place.

We may have come a long way for women in science and STEM since Frances Oldham Kelsey stood up, confident in her own abilities to save lives, but there’s still a long way to go. As demonstrated by the two media storms I mentioned earlier, there is still a gap between what is done and what is thought. Both eminent scientists caught up in the public outing of gender discriminatory conventions thought nothing of casually wearing softcore to a media event or reducing adults to juvenile status just because they’re female.

Oh—and it was a joke.

Seriously?

Well—I’m sure that thousands of U.S. mothers in the 1960s were really happy that Frances Oldham Kelsey could take the joke and keep her mind focused on the job at hand rather than buckle and leave, as many women girls in STEM do. Hmmm—makes you wonder how many amazing breakthroughs in science have been missed because the girls couldn’t take the joke any longer?

Catch up with more Ada Lovelace posts from around the world here.

If you are in Vancouver, B.C., Telus World of Science is holding an Ada Lovelace/Women in Science–themed series of STEM talks on October 13, 2015. If you miss it this year, perhaps sign up for their mailing list so you don’t miss it next year.