Engineers at Cornell University presented work on smartphone-based medicine at CLEO: 2013 last month, the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics. Their creation is an external device that connects to a smartphone and can be used to diagnose Kaposi’s sarcoma and a slew of other serious conditions. Based on the press release, the smartphone itself isn’t doing any sensing. Instead, it acts as a lightweight and (relatively) low-cost computer that analyzes the input from the external device and displays the results to the user.

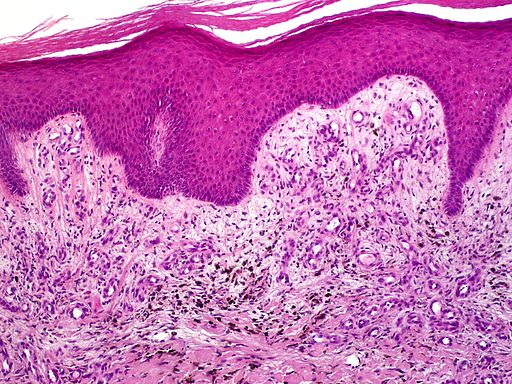

The emphasis on detecting Kaposi’s sarcoma is interesting, since the condition typically doesn’t manifest until HIV has progressed to AIDS. In places where Kaposi’s sarcoma is much more widespread and where other methods of detection are less available, this tool could be extremely valuable as a way of securing a definitive diagnosis: not everyone with AIDS develops Kaposi’s sarcoma, but Kaposi’s sarcoma is an extremely reliable indicator of AIDS.

The emphasis on detecting Kaposi’s sarcoma is interesting, since the condition typically doesn’t manifest until HIV has progressed to AIDS. In places where Kaposi’s sarcoma is much more widespread and where other methods of detection are less available, this tool could be extremely valuable as a way of securing a definitive diagnosis: not everyone with AIDS develops Kaposi’s sarcoma, but Kaposi’s sarcoma is an extremely reliable indicator of AIDS.

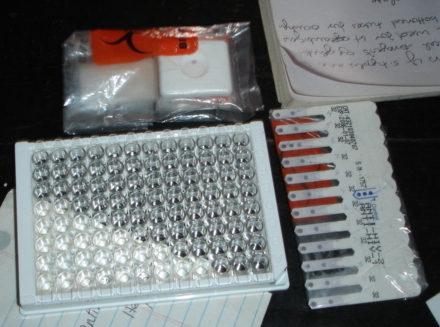

The researchers are also promoting this setup for other conditions: syphilis and MRSA are both possible targets, and MRSA in particular seems like a big deal, since it’s frequently transmitted in hospitals and can be extremely lethal in that context. A 2006 study at a South African hospital found that 33 per cent of patients clinically suspected of having MRSA died within two weeks.1 Perhaps most significantly, the device (or at least devices like it) could be used to perform the widely used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, or ELISA, a test used to detect multiple infections including hepatitis, E. coli, and HIV.

The researchers also emphasize that their system is usable by people without extensive medical training. This could be a huge asset, but also comes with many questions and potential drawbacks. We’ve written before about controversies over the ethics of doing citizen science with medical information. While it would be pretty amazing to be able to do some of your own lab work at home without having to a) go to med school and b) live at your med school, the social dynamics around disease and medical information in general are hard to predict.

The researchers also emphasize that their system is usable by people without extensive medical training. This could be a huge asset, but also comes with many questions and potential drawbacks. We’ve written before about controversies over the ethics of doing citizen science with medical information. While it would be pretty amazing to be able to do some of your own lab work at home without having to a) go to med school and b) live at your med school, the social dynamics around disease and medical information in general are hard to predict.

There’s also another problem with decoupling medical tests from medical establishments. The prevalence of fake or expired malaria medication in Africa is a serious threat to public health efforts, and scams targeting HIV patients have been around for years now. And of course, stigma is always a concern in the context of HIV/AIDS. Even if citizens can accurately test for HIV, what mechanisms will protect the data generated by this testing, and ensure its integrity?

I mention all of this only because I think it’s important to assess new devices in context to the extent that we can. That said, I don’t think these are problems for the engineers responsible for this device. They’re problems for ethicists, medical professionals and citizen science pioneers. And even if we make some accurate predictions at first, it seems likely that an invention like this will still end up surprising us somehow.

1 Perovic, O., Koornhof, H., Black, V., Moodley, I., Duse, A., & Galpin, J. (2008). Staphylococcus aures bacteraemia at two academic hospitals in Johannesburg. South African Medical Journal, 96(8), 714. doi:10.7196/samj.1201