If you were around during the late seventies or early eighties, you grew up knowing that insects will inherit the Earth after the nuclear apocalypse. However, apart from mad survival skills, did you know that they also beat us at engineering?

Researchers at the University of Cambridge in England have found that the jumping bugs Issus coleoptratus use gear cogs in their hind legs to coordinate jumping movements. Even though these gears aren’t the kind I’ve been using recently to ratchet myself up and down the Valley Trail in Whistler, the cogs uncovered by the research team look uncannily similar to those on my bicycle. What’s more, the insects were on the ball about this long before Messrs. Da Vinci et al. came up with the idea.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge in England have found that the jumping bugs Issus coleoptratus use gear cogs in their hind legs to coordinate jumping movements. Even though these gears aren’t the kind I’ve been using recently to ratchet myself up and down the Valley Trail in Whistler, the cogs uncovered by the research team look uncannily similar to those on my bicycle. What’s more, the insects were on the ball about this long before Messrs. Da Vinci et al. came up with the idea.

Senior investigator professor Malcolm Burrows, from Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, first became interested in these tiny plant hoppers while visiting a colleague in Aachen, Germany. On his return to the UK, Burrows, whose research interests include investigating neural control and coordination of jumping, searched in vain for the insects. The Issus species he was looking for feed only on ivy, and none of the bushes he searched through in Cambridge contained the insects. Burrows only struck lucky when he enlisted his family in the hunt: the bugs he was looking for were in his five-year-old grandson’s back garden.

Back in the lab, Burrows and co-author Gregory Sutton used high-speed imaging to break each moment of the insect’s jump into frames. They found that the hind legs of the Issus moved within 30 microseconds of the other, generating an explosive acceleration of 5 metres per second in less than a millisecond, propelling the insect through G-forces of around 500 to 700.

But how? Burrows knew that this was not purely the result of neuronal firing; it takes too long for the nerves to fire up each leg’s muscles in synchronized movement. One misstep, and the flightless bug would head off askew in a jump, its sole means of getting around–and wobbly flights are not a feature of Issus locomotion.

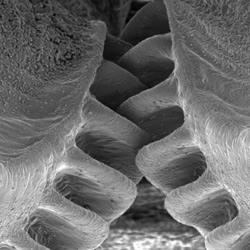

The answer came from examining the anatomy of the insects, or more correctly, the structure of the nymphs or juvenile forms of the Issus. Elegant high-magnification images showed sophisticated gear teeth arranged to interlock neatly with opposing teeth at the top of each hind leg or trochantera. The gear teeth even had rounded corners, a feature seen in man-made cogs to reduce the potential for breakage or other damage.

As the nymph prepares to take a leap, the exoskeleton arches, and the 400-micrometre cogs engage. At the start of the jump, the intermeshing teeth ensure that both hind legs act simultaneously. In other words, when one leg moves, the other is kicked into action in the same direction. This prevents what is termed “yaw rotation,” where only one leg propels the Issus and the insect spirals off course through the ivy.

Burrows and Sutton think that only the juveniles need cogs to get going, since they lack the strength of the larger adults. Also, since the nymphs moult between stages, damaged cog teeth are replaced much more easily than in the terminal adult stage. A missing cog tooth spells disaster for synchronized effort.

Whatever the reason, the Issus nymphs and their trochanteric cogs are now part of scientific history as the first living version of functional mechanical gears in the animal kingdom.

Amanda Maxwell has just joined Talk Science to Me as a copywriter. We’re excited to showcase her work. Welcome aboard, Amanda!

well written and super interesting!

Thanks Christi – glad you enjoyed reading it. Such a neat investigation, and awesome images as the added bonus.

Comments are closed.