I don’t often leave a six-hour seminar with more energy than when I came in, but if it’s six hours of language stuff, I’m pumped. This past Saturday the BC branch of the Editors’ Association of Canada hosted a workshop called Eight Step Editing, delivered by veteran editor and writer Jim Taylor, who developed the program in the 1980s. Jim has taught this process literally for as long as I’ve been alive, and I soaked up all the expertise I could. Eight Step Editing provides a framework for the editing process, a systematic way to approach editing that begins with making the fewest changes to the author’s words and becomes progressively more in-depth. I won’t go into the eight steps (you can find a good summary here), but I will share with you what got me so excited.

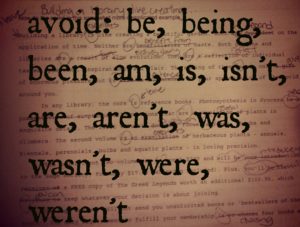

In step 5, “Eliminate the Equations,” Jim proposes that sentences have energy, and that this energy depends on their verbs. Of course this makes sense, because verbs usually express some sort of doing, so by definition they normally require some energy. But Jim doesn’t mean energy that comes from the meaning of a word; he argues that sentences have intrinsic energy that results from their structure and word choice: grammatical energy. Grammatically, “laze” is just as energetic a word as “sprint.” And the verb that most sucks the energy out of a sentence? To be and, by extension, its variants: being, been, am, is, isn’t, are, aren’t, was, wasn’t, were and weren’t.

Hearing that I should avoid is made me feel the same as when the doctor told me I should stop eating rice or when Stephen King told me to shun adverbs. No rice? No adverbs? No is? But these are staples!

Jim calls to be verbs “equating verbs,” traditionally known as copular or linking verbs. He writes:

“Equating verbs equate. They do exactly the same thing as an equals sign in a formula. And that’s all they do, regardless of the complexity of the sentence or the thought that it contains.”

By not doing anything, equating verbs, those little grammatical vampires, suck the energy out of a sentence.

Because it wants to belong to an equation, is often looks for a noun, and if it can’t find one, it’ll grab the nearest verb and morph it into noun form. Now, of course there’s nothing wrong with nouns (in Jim’s words, a noun is the anchor and verbs are the sails). But writing and language experts agree—to some extent—that writers should avoid nominalizations, or zombie nouns (though the deeper you go linguistically, the less clear-cut the issue becomes). Jim’s reminder to reduce nominalizations is not original, but looking at the verb instead of hunting for nouns is a fresh approach for me.

Linked to the problem of energy-sucking verbs, the issue of active and passive voice has popped up in every language, linguistics, writing and editing class I’ve ever taken. A passive sentence by definition requires a to be component, but I’ve never thought of to be as something I should watch for in active sentences as well—honestly, I’ve never really thought of to be at all.

While Jim advocates reducing the use of to be verbs, he doesn’t encourage trying to get rid of every single one in a document—a rather futile task. Instead, he suggests looking for clusters of to be variants, especially more than one in a sentence, or two to be–dependent sentences close together. Some sentences change easily: “My love for Vancouver is a reflection of my land-locked prairie childhood” becomes “My love for Vancouver reflects….” But some take more work: “Vancouver is the largest city in BC” can only change if you can add an appositive and attach it to the next sentence: “Vancouver, the largest city in BC,….” Sometimes it just creates an awkward mess, and we have to exercise common sense.

Jim suggested that we choose one step out of the eight to focus on and apply to our work until it becomes second nature. De-ising my life will take a very long time, but, what do they say? You have to expend energy to save energy?

So, in the name of energizing, I did a little discourse analysis. The first draft of this post came in at 602 words and had seven is’s, four been’s, five are’s, and one being (not including the ones I referred to as nouns). I had 17 to be variants in 602 words, which felt like a lot, especially considering that I had challenged myself to avoid them altogether when I sat down to write. But as we all know, writing isn’t editing. So I edited. Final tally? 702 words, 14 to be variants. Still more than I’d hoped, so I re-edited. Final final count? 844 words, 10 to be’s. Energy well spent.

Your turn: take the last thing you wrote and search for is and its friends. Then edit and edit again, like I did, until bedtime—you’ll find yourself going to sleep with some grammatical garlic hanging around your neck.