Repeat after me: correlation does not imply causation

In April, the Journal of Neuroscience published the paper that apparently everybody had been waiting for—definitive proof that even recreational cannabis use messes with your head. As soon as the publication embargo lifted, the headlines screamed into action, suggesting the danger to developing brains from just a few puffs of weed per week. According to the press release from one of the associated research institutions, casual marijuana use was linked to brain abnormalities—“more ‘joints’ equal more damage.” Even the paper’s senior author, Hans Breiter, questioned the safety of pot use in anyone under the age of 30.

But is this really what the paper’s results showed?

No.

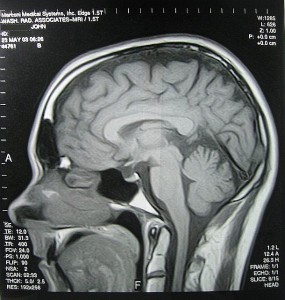

The study, cross-sectional and retrospective in design, used MRI scans to compare brain morphology of 20 self-reported recreational 18- to 25-year-old marijuana users with appropriately matched controls. At a single interview, each subject estimated their cannabis consumption over the previous 90 days and underwent an MRI scan.

From the results of the neuroimaging interpretations, the researchers found that there were indeed differences in certain areas of the brains of the marijuana users compared with their matched controls at the time the scans were taken. The intensity of these differences also varied according to the self-reported cannabis intakes in the users—heavier drug use correlated positively with more pronounced changes. Although changes were evident, the authors state at the start of the paper’s discussion that their study group was not large enough and their experimental design was insufficient to determine what caused them.

However, this is not what was widely reported. Instead, headlines announced that recreational pot use damaged young people’s brains. Perhaps the focus was on the abstract, the thumbnail of text at the start of a scientific paper that gives readers a sneak peek at what it’s all about, where the authors state, “These data suggest that marijuana exposure, even in young recreational users, is associated with exposure-dependent alterations of the neural matrix …” Or maybe the writers were swayed by the press release quoting the senior author. … suggests … associated with …

Correlation does not imply causation.

In statistical analysis, correlation indicates the degree of linear relationship between two variables. It is usually calculated as a correlation coefficient, and the closer it is to 1 or -1, then the stronger the linear relationship is. Conversely, a correlation coefficient closer to zero implies that there is no linear relationship between the two variables. Plotting heights against weights for a large sample of the human population will show that they correlate very strongly, in that taller people are usually (though not always) heavier than their shorter neighbours.

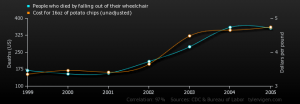

But just because two factors correlate well, it doesn’t mean that one causes the other – being tall doesn’t necessarily make you heavy. For example, comparing the price of a bag of chips with wheelchair deaths annually between 1999 and 2005 gives a strong positive correlation coefficient of 0.971706. But does paying more for 16 ounces of potato chips really increase the number of wheelchair users falling to their deaths?

Correlation only, not causation.

Changes were observed, but since only one MRI scan was performed, the data do not show whether cannabis was responsible. Moreover, the scans only provided a snapshot, a freeze-frame reference to one moment in time. Certainly, the cannabis users’ brains differed from the control group’s, but what did they look like before starting to smoke pot? Could specific brain morphology predispose individuals to start smoking pot? Or could something else have caused the changes? Alcohol perhaps?—all the subjects in the user group reported higher alcohol consumption than their matched controls. Furthermore, the brain changes seen in the cannabis users were not assessed for impact on function or behaviour, so are they really associated with damage?

All of these factors need further investigation—the authors themselves state that more in-depth studies are needed, and expressed a degree of frustration in the media response. This still, however, leaves a confused readership, who may or may not be lighting up to cope with the stress.

Admittedly, it is very tempting to go after the sensational clickbait headline, especially online where clicks mean advertising bucks. However, as science communicators we have a duty of care towards a lay audience, to present facts in an engaging, easily understood but accurate format.

Sensationalism has no place—implying causation from correlation is not the way forward.

Reference

Gilman, J.M. et al. (2014) “Cannabis Use is Quantitatively Associated with Nucleus Accumbens and Amygdala Abnormalities in Young Adult Recreational Users“, The Journal of Neuroscience 34 (pp.5529 –5538)

Further Reading

- More wacky correlation/causation fun at http://www.tylervigen.com/

- Guidance from The Science Writer’s Handbook http://pitchpublishprosper.com/power-pitfalls-correlation/

- Analysis from UK’s NHS Behind the Headlines http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/behindtheheadlines/news/2014-04-16-cannabis-linked-to-brain-differences-in-the-young/

- A note on the statistics from a computational biologist working in genomics http://liorpachter.wordpress.com/2014/04/17/does-researching-casual-marijuana-use-cause-brain-abnormalities/