Science papers—the everyday tales of slaying research dragons and finding buried treasures. Not just for stereotyped nerds in white coats, or wild-haired Einstein lookalikes. You can read them too. With the rise in open access publishing, more are available to lay readers outside academia’s ivory towers.

Science papers—the everyday tales of slaying research dragons and finding buried treasures. Not just for stereotyped nerds in white coats, or wild-haired Einstein lookalikes. You can read them too. With the rise in open access publishing, more are available to lay readers outside academia’s ivory towers.

But what are they all about? And why would you want to read one?

Firstly, there are two types of science papers: primary research, where excited doctoral students and their senior advisors showcase their latest research and launch it into the international science world, and reviews, which round up current knowledge and up-to-date thinking in one subject area. Although the reviews give a broad overview of the current state of scientific play, the primary research papers are the ones that generate the excitement with their sensational headlines.

And this is the reason you might want to take a peek at the primary source material itself—is the headline a fair summary of the paper? Is the press release an accurate representation of the research?

Although daunting to non-scientists (and also to scientists not working in the field itself—just because we’re scientists doesn’t mean we understand every little bit of science), they’re not difficult to read, though it might take a little time. However, even real scientists go through a research paper several times, making notes and paying attention to comprehension. So you’re not slow or dim or uneducated if you need to read it more than once.

What is a primary research paper?

Primary research papers draw together a project or sub-project, announcing its results to a waiting audience of peers. They are usually submitted to and published by peer-reviewed journals, where the editorial process involves close scrutiny by experts active in the field. They make suggestions on style, writing quality and content; criticise experimental design and data analysis; correct errors; and request clarification, revision or even extra experiments before publication.

Why write primary research papers?

Glory? Staking a claim? Announcing an earth-shattering piece of scientific news? Documenting the process?

All of the above—a publication is the equivalent of a news piece announcing experimental results, and it also establishes ownership or primacy. A doctoral student may need a certain number of publications for a thesis. Publication is often a requirement for grant funding, academic tenure and general career advancement.

What’s inside?

Primary research papers usually start with an abstract, then move into the introduction, materials and methods, and results, ending with a discussion of the work’s significance. A list of references, listing all the papers consulted in designing the experiment and analysing the results, follows, and there may be some kind of disclosure regarding affiliations, funding and so on. A beginning, a middle and an end.

Where do I start?

The abstract is an obvious place to start, but beware—this part is the foreword, the marketing paragraph designed to pull the reader in with all the juicy bits. It is a summary, highlighting all the key findings and usually with a tightly restricted word count. This is where you can see if the subject interests you—just don’t stop here.

Move on to the introduction, where the scientists answer the “Why?” behind their experiments. What made them research this particular problem in this particular way? Introductions usually summarise background material, giving a history of research in the subject and the reasoning behind a scientist’s interest. This is where you will find their quest, what makes them tick as a researcher. Look closely; there is nearly always a plot to follow.

Materials and methods is where you find out “how,” and it may seem like it is written in a completely foreign language…these are merely the tools a scientist takes on the quest, a little like some of the awesome text-driven role-playing games of early internet years. For “96-well plate,” read lump of coal, or short sword. They help get the job done, though might not be so good at fighting off dragons.

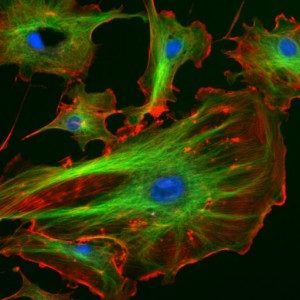

The results section is where you find out what happened on the quest itself. There will be lots of numbers, graphs, percentages and statistical analysis. If you’re lucky there will also be cool MRI scans, pictures of fungal growth and fluorescently labelled cells, and invertebrates . It can also be where the story gets exciting—what dragons were vanquished during the quest? If odd results come up or something didn’t work, the research team needs to find out why and explain how they accomplished this. With a well-written paper, knowing the methodology is unimportant—there is a definite beauty in the logical flow of a well-designed experiment when the writer takes the time to explain why step A follows step B and leads into step C. Each stage enhances the results in the previous, rounding out the research and complementing the experimental design…it reads like an expertly crafted narrative with plot development at every turn.

The results section is where you find out what happened on the quest itself. There will be lots of numbers, graphs, percentages and statistical analysis. If you’re lucky there will also be cool MRI scans, pictures of fungal growth and fluorescently labelled cells, and invertebrates . It can also be where the story gets exciting—what dragons were vanquished during the quest? If odd results come up or something didn’t work, the research team needs to find out why and explain how they accomplished this. With a well-written paper, knowing the methodology is unimportant—there is a definite beauty in the logical flow of a well-designed experiment when the writer takes the time to explain why step A follows step B and leads into step C. Each stage enhances the results in the previous, rounding out the research and complementing the experimental design…it reads like an expertly crafted narrative with plot development at every turn.

And on to the finale! Discussions can be useful, adding more knowledge and insight into the results. Alternatively, this section can be a deathly dull listing of “we found this; it does that” statements. A well-written paper places the experimental results within a broader context, giving them relevance and personality. This is where the research team shows that they understand the true meaning of their quest, whether they accomplished it or not. Has the True Meaning been discovered or is more questing required?—the authors should say so, rather than exaggerate false claims or inflate their findings. The final paragraph should be a neat summary and conclusion leaving the reader replete, satisfied and somewhat more knowledgeable than when they started.

So, how do I know if a paper is valid?

This is tricky. Unless you’re active within the field or have a good grasp of experimental design and statistical analysis, you probably won’t be able to analyse it in depth. But there are things you can pick up on that might give you a clue.

Does the abstract (or the press release) accurately reflect what is in the paper and the authors’ conclusions in the discussion?

Check out the references—depending on the uniqueness of the research, the following questions may be justified: Do the references seem valid? How recent are they? How many sources have the authors consulted, or do they just stick with their own work? Are they citing credible journals?

And the disclosure—How valid is a study on glucose-fructose funded by a large soft drinks manufacturer? Is the research sponsored by a strong advocacy group? Where is the grant from? Who does the senior author (usually the last person listed as an author) work for?

So next time you see a sensational headline announcing that if more people did XYZ then they wouldn’t die from diseases A, B or C, have a look for the primary source material and translate it for yourself.

Further reading

Getting your hands on primary research papers:

Open access publishers like Public Library of Science, PLOS ONE and eLife are a ready source of peer-reviewed primary research papers. Other publishers may also make papers available online without requiring subscription or erecting a paywall. Your library subscription (academic or public) often gives access to papers for free if you don’t want to purchase access. Googling the paper’s title sometimes works too.

How to read a science paper—some great advice below:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jennifer-raff/how-to-read-and-understand-a-scientific-paper_b_5501628.html

Reading critiques of research papers

Want to see how scientists analyse published research results? Learning from professionals in action is a good way to hone your own observational skills. Check out the PubMed Health home page from the National Library of Medicine, or pay a visit to the UK’s National Health Services Behind the Headlines service.

Check out Ben Goldacre’s acerbic takedowns of bad science in The Guardian.

Spotting errors

As mentioned, this is difficult, but if you’d like to learn more about appropriate application of statistical analysis, try Lior Prachter’s blog. And if you like infographics, Compound Interest’s Everyday Exploration of Chemical Compounds blog has a great poster, A Rough Guide to Spotting Bad Science.

The post’s author reviews two to three primary research and review papers each week, distilling the storyline into engaging summaries for one of Talk Science To Me’s clients, Go Communicate, over on Accelerating Science. After a year and more than 100 reviews, Amanda feels confident that she can find the hidden narrative behind any protein chemistry paper or food safety technique.