We’ve covered Ada Lovelace Day on the Talk Science blog for the last couple of years. By now, dear reader, you should know all about the “Enchantress of Numbers,” as Charles Babbage referred to her, and why her achievements are so remarkable even today.

We’ve covered Ada Lovelace Day on the Talk Science blog for the last couple of years. By now, dear reader, you should know all about the “Enchantress of Numbers,” as Charles Babbage referred to her, and why her achievements are so remarkable even today.

But who came before her—who paved the way?

And this is where I launch into another of my favourite themes: coincidences. It turns out that one of Ada’s teachers grew up only a few miles away from my childhood home, 200 years before me.

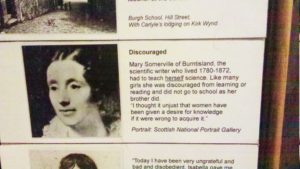

Meet Mary Fairfax Somerville (1780–1872), a fellow Scotswoman who grew up in Burntisland on the south coast of Fife. As Mary was a girl growing up in the late 18th century, her education was limited to only what was appropriate for her gender: needlework, social skills and very little else, since otherwise would have been wasteful.

However, Mary had other ideas. After a disastrous year at a boarding school for young ladies, she set out to educate herself, learning Latin and mathematics on the fly by reading every single book in the house. When the family moved to Edinburgh, her art teacher, Alexander Nasmyth, let slip that in addition to being a great reference for understanding perspective in paintings, Euclid’s Elements of Geometry was also a way in to astronomy and science in general. Her two brothers received a full grounding in science and mathematics, so Mary managed to convince their tutors to help her in her studies too.

However, Mary had other ideas. After a disastrous year at a boarding school for young ladies, she set out to educate herself, learning Latin and mathematics on the fly by reading every single book in the house. When the family moved to Edinburgh, her art teacher, Alexander Nasmyth, let slip that in addition to being a great reference for understanding perspective in paintings, Euclid’s Elements of Geometry was also a way in to astronomy and science in general. Her two brothers received a full grounding in science and mathematics, so Mary managed to convince their tutors to help her in her studies too.

Her first marriage lasted three years and was to a man who was not interested in the idea of women educating themselves or maintaining an interest in science. Her second was more supportive; during this time, Mary sharpened her mathematics skills, holding discourse with the day’s experts and publishing papers on astronomy and physics. In addition to predicting the presence of Neptune through its influence on the orbital path of Uranus, Mary taught mathematics to the Baroness Wentworth’s daughter, Ada Lovelace, and eventually introduced her to computing pioneer Charles Babbage.

And the rest, as they say, is history, with Ada Lovelace Day rolling around each year to encourage women and girls that the STEM life is attainable regardless of gender.

Although science was not completely the norm for girls while I was in high school, I certainly wasn’t discouraged in the way that Mary was growing up, and I had many more role models to inspire me. While I’m not sure entirely who inspired me to go into science, the coincidence of Mary Somerville growing up in the next village along the coast would have been meaningful—if I had known about her. I only found out her about when visiting the local museum. Women in science history are mostly invisible. For example, Fanny Hesse. Without her contribution, microbiology would struggle.

This is an issue currently being addressed by Emily Temple-Wood, who is meeting another discrimination that women in STEM face with proactive editing. For every offensive tweet or email she receives, she creates a Wikipedia entry for another woman in science. Since women who dare to voice an online presence get a disproportionate amount of hate, threats and sexual abuse directed at them, Temple-Wood is very busy. Check out the Women Scientists WikiProject page for details, and if you’d like to hack in good company, search out one of the many edit-a-thons for Ada Lovelace Day, like this one at the University of Edinburgh, my alma mater.

And this is probably as good a reason as any for the continuation of Ada Lovelace Day—promoting women’s place in science, past, present and future. Maybe I would have found out about Mary Fairfax Somerville a little sooner if women scientists were more revered throughout history.

Finally, another coincidence: translation.

According to her Wikipedia entry, Mary Somerville described her work as translation: “I translated Laplace’s work from algebra into common language.” In addition to our childhood homes, it’s something else we share and gives me inspiration in hindsight. For me, translating science into easily accessible nuggets is a common theme running through my science career and is the reason why I now proudly call myself a science writer.