Repeat after me: correlation does not imply causation

In April, the Journal of Neuroscience published the paper that apparently everybody had been waiting for—definitive proof that even recreational cannabis use messes with your head. As soon as the publication embargo lifted, the headlines screamed into action, suggesting the danger to developing brains from just a few puffs of weed per week. According to the press release from one of the associated research institutions, casual marijuana use was linked to brain abnormalities—“more ‘joints’ equal more damage.” Even the paper’s senior author, Hans Breiter, questioned the safety of pot use in anyone under the age of 30.

But is this really what the paper’s results showed?

No.

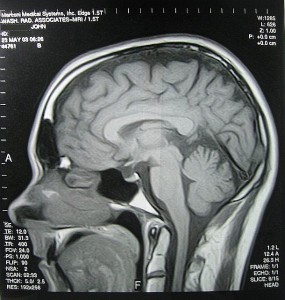

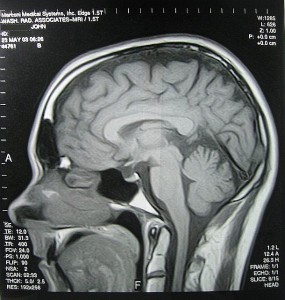

The study, cross-sectional and retrospective in design, used MRI scans to compare brain morphology of 20 self-reported recreational 18- to 25-year-old marijuana users with appropriately matched controls. At a single interview, each subject estimated their cannabis consumption over the previous 90 days and underwent an MRI scan.

From the results of the neuroimaging interpretations, the researchers found that there were indeed differences in certain areas of the brains of the marijuana users compared with their matched controls at the time the scans were taken. The intensity of these differences also varied according to the self-reported cannabis intakes in the users—heavier drug use correlated positively with more pronounced changes. Although changes were evident, the authors state at the start of the paper’s discussion that their study group was not large enough and their experimental design was insufficient to determine what caused them.

However, this is not what was widely reported. Instead, headlines announced that recreational pot use damaged young people’s brains. Perhaps the focus was on the abstract, the thumbnail of text at the start of a scientific paper that gives readers a sneak peek at what it’s all about, where the authors state, “These data suggest that marijuana exposure, even in young recreational users, is associated with exposure-dependent alterations of the neural matrix …” Or maybe the writers were swayed by the press release quoting the senior author. … suggests … associated with …

Read More »Caveat lector or reader beware!

Science papers—the everyday tales of slaying research dragons and finding buried treasures. Not just for stereotyped nerds in white coats, or wild-haired Einstein lookalikes. You can read them too. With the rise in open access publishing, more are available to lay readers outside academia’s ivory towers.

Science papers—the everyday tales of slaying research dragons and finding buried treasures. Not just for stereotyped nerds in white coats, or wild-haired Einstein lookalikes. You can read them too. With the rise in open access publishing, more are available to lay readers outside academia’s ivory towers.

Christie Aschwanden has

Christie Aschwanden has